Caer Llan, view from the Driveway

The last time I drove a rental car in the United Kingdom, it was to get to a Welsh cultural festival. Recent Hiram College graduates Tim Walker, David Cornicelli, and I were in Wales working for the summer, helping to build a passive solar-heated, earth-sheltered extension to the Caer Llan Field Study Centre. This was 27 years ago. We had come as graduate students to pitch in on the environmentally visionary project, and to spend a summer surrounded by the ruined castles and abbeys of the Wye river valley and nearby black hills, and to drink the beer. One weekend we heard about this cultural festival, the Welsh National Eisteddfod, so we figured we’d rent a car for the weekend and drive up to hear the famous choirs.

Caer Llan, view from the back garden.

Back then, to rent a car in a foreign country, a person needed an international drivers license. David had an expired one, which he’d brought with him from the US for no good reason, but he didn’t bring it along when we went to pick up the rental car. After all, it had expired. Why bother? But when we arrived at the rental place in Monmouth, the proprietor wouldn’t give us the car without the proper paperwork.

“Dear Peter, I want to build a wall. Love, David.”

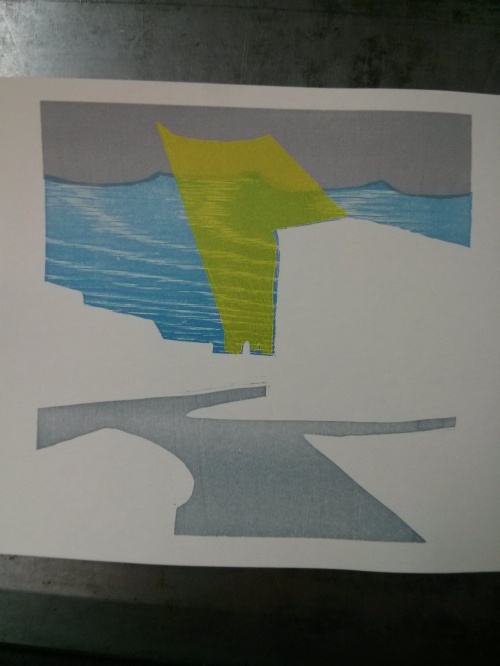

View from the Berm House roof

“We forgot to bring it,” we told him. “We’ll be back.”

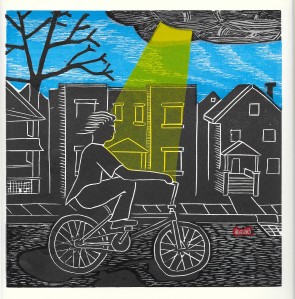

So we went back to Caer Llan to see if we could figure out some plan to rescue our weekend: No license, no car, no choirs. None of the anticipated road trip debauchery. So David took out the old license, a slightly worn document three years expired. And we noticed that it was made only of heavy paper, no laminating, no photo ID. And further, that at the bottom, just below the expiration date, there was some left over free space. We happened to have some US coins in our pockets. So there was borne an idea.

A US quarter would do the trick. We laid it down on a block of wood, and the driver’s license down on top of it, and a heavy rag down on top of that, and then another block of wood. We popped the whole sandwich with a big hammer from the construction site, embossing the page with the very official looking profile of George Washington. In God We Trust. We got a black pen and a ruler, and next to the improvised notary stamp we drew a line. We wrote in a new expiration date. We signed it “Richard Shagnasty,” in a script so sloppy as to be illegible to anyone who didn’t know.

Double rainbow, full arc, right the whole way across the landscape below Craig Y Dorth.

This was satisfying work. We showed it to our host and employer, Peter Carpenter, who –despite the position in which our expatriate criminal activity might put him—had that usual gleam in his eye. “I’ll either see you in a few days, or I’ll see you in jail,” he said.

We picked up the car without a hitch. The lending agent didn’t look twice. We drove through the night to Porth Madoc, the town in North Wales where the Eisteddfod was held. We drank the local beer. We slept in the car. We met some Welsh women. At no time did the the police intervene.

*

These days you don’t need an international drivers license to rent a car in the United Kingdom. I know this because twenty seven years after that summer at Caer Llan—last week–I went back. I took a short break from an artist residency in Germany to catch up with Peter, his son Jake and

With Peter Carpenter, the visionary who conceived the Caer Llan Field Study Centre, and designed and built the earth-sheltered berm house there.

family, and to see the beautiful place we had helped, in the smallest way, to build. What I feel looking at the place –more than pride in my tiny role there–is massive gratitude for having been involved in such a visionary project, with such capable and generous people.

Caer Llan was originally built as a private house at the turn of the 18th to 19th century, overlooking pasture land marked off by hedgerows undoubtedly older. It was enlarged over the years, but as fortunes ran down in the twentieth century, so did the house. In the sixties it was being run as a small boarding school, and it came up for sale. Peter Carpenter was teaching biology and leading his students on field study excursions at the time. Circumstances aligned, and he bought the place in 1969 with a plan to make it a field study center—a place for student groups to come and stay while they studied through the lens of the surroundings: The English majors would visit the ruin of Tintern Abbey, famous as the place in the Wye valley above which William Wordsworth wrote his famous lines. Perhaps they would take in a bit of Shakespeare in the courtyard at Raglan Castle. The history students might do that, and look at Chepstow and other castles, and any of the significant prehistoric stones that can be found nearby. For the biology students, there are peat bogs. For everyone, plenty of English beer.

The passive solar-heated extension followed. Timothy, David, and I originally met Peter on Hiram College trips to Cambridge, which stopped at Caer Llan. That was in the early 80s. The berm house was an unfunded vision then. But a few years later, we learned that Peter had cut a deal with a retired submarine commander, who pledged enough money to get the project moving, in exchange for being able to live there in his remaining years. So we wrote Peter letters, telling him we’d give a summer’s labor in exchange for lodging and food. By then it was 1987.

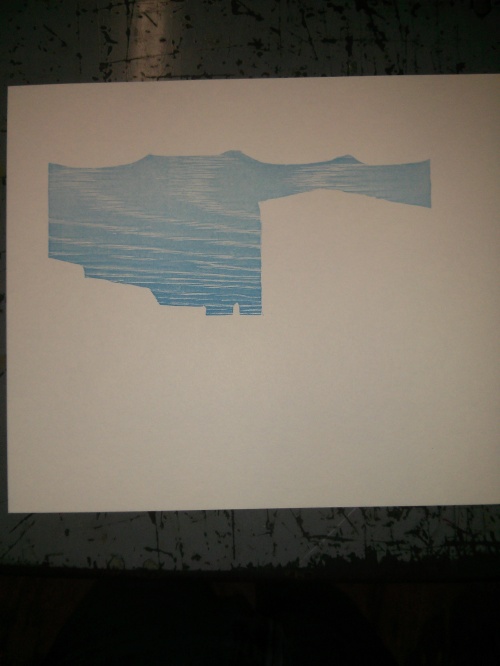

Caer Llan was among the first (if not the first) passive solar heating structures in the United Kingdom. The modern addition uses recycled stone to match the original house, and does not

The ol . . . as in late 13th/early14th century . . . church at Penalt.

obstruct the view of its façade or any of its other sides. Castellations and other features are complementary. Built into the side of a hill, it has southwest-facing, double paned windows and hyper insulated walls. To top it off, it is covered with six feet of earth, atop which are planted a lawn and garden. A BBC news program once featured Peter mowing the roof. The idea and reality of the construction are that for the majority of the year it is heated and cooled by just a single fan that draws in fresh air, warms it in the solar corridor, and vents it in and out of the rooms. Only in the coldest months do rooms require a little boost from a space heater.

Garden vistas abound. This one ends with a foot path through the woods, toward a former pub called The Gocket (now a private home) and beyond.

In the years since I worked there, Peter has handed the place off to his son Jake and his wife Vicky to run. Caer Llan has evolved under their leadership to keep up with the changing economy. Instead of students sleeping in bunk rooms with group bathrooms, eating meals prepared by live-in help, the place caters to weddings and business conferences, offering five-star group lodging.

For my return visit, my rental car travels were not quite as eventful as the first time around. I picked up a nice Vauxhaul at Stansted airport at about midnight, and set off, guided by a GPS I borrowed from an artist friend in Dresden, Kerstin Franke-Gneuss. I made one wrong turn, landing eventually on two-lane “A” road that took me through Oxford, Ross-on-Wye, and about 47 thousand roundabouts. After a three-hour trip that took me five, I rolled up the driveway at Caer Llan at about 5 a.m.

Chris, the senior gardener, then and now.

The Welsh countryside is still there, including the hilltop known as Craig Y Dorth, with incredible views over small farms, delineated by ancient hedgerows and populated by sheep and cows. I walked around it a couple of times, and saw the full arc of a double rainbow there the day I arrived. Peter Carpenter chauffeured me to the 13th/14th century Old Church in Penalt, which was one of my walking destinations a quarter century ago. I’d have walked this round, too, but for lack of time in a three-day visit. Other destinations back then and now included the old parish churches of Mitchell Troy and Trellech; the Virtuous Well of Trellech and Harold’s Stones nearby; the town of Monmouth with its old fortified bridge; and, in a quick stop on the way back to London, Tintern Abbey.

With Jake Carpenter and Vicky Carpenter, who run the place now.

All this, obviously, is illustrated with photos from the trip. Huge thanks to Peter, Jake, Vicky, Charlotte, and Georgia for unparalleled hospitality. Here’s hoping the next time takes much less than 27 years.

The phone booth at the end of the drive, with phone still operative.

The road around Craig Y Dorth–a walk of a mile or two, with glorious views of the green Welsh countryside.

Returning to Caer Llan on the footpath that leads to pastures behind what used to be a centuries-old local pub on the road from London to Monmouth, the Gockett.

Steps in the garden

Tintern Abbey

The Virtuous Well of Trellech, a destination for pilgrims ho came for its healing properties, fed by water from four springs.